“Some medals aren’t to be worn on your shirt but on your soul.” (Gino Bartali)

Gino Bartali is best known as one of the greatest Italian riders of all time. He performed the incredible feat of winning the Tour de France twice with a ten year gap in between. His victories came in 1938 and 1948 while Europe and the wider world was torn apart by the ravages of war. Like many cyclists from that period, he was unable to make the most of his prime years. That didn’t stop him accruing the most impressive palmarés that includes, as well as those two Tour de France victories, three Giro d’Italia, three Lombardia and four Milan – San Remo titles. He is regarded as one of Italy’s greatest sporting heroes as a result.

And of course, everyone thinks of his rivalry with Coppi, so intense that some have commented that they seemed less interested in winning the race itself than in beating each other. But, as well as being one of the most adored sportsmen of all time, ‘Gino the Pious’, as he was known, has more recently been recognised as a war hero who helped save the lives of as many as 800 Jews under the Nazi occupation of Italy.

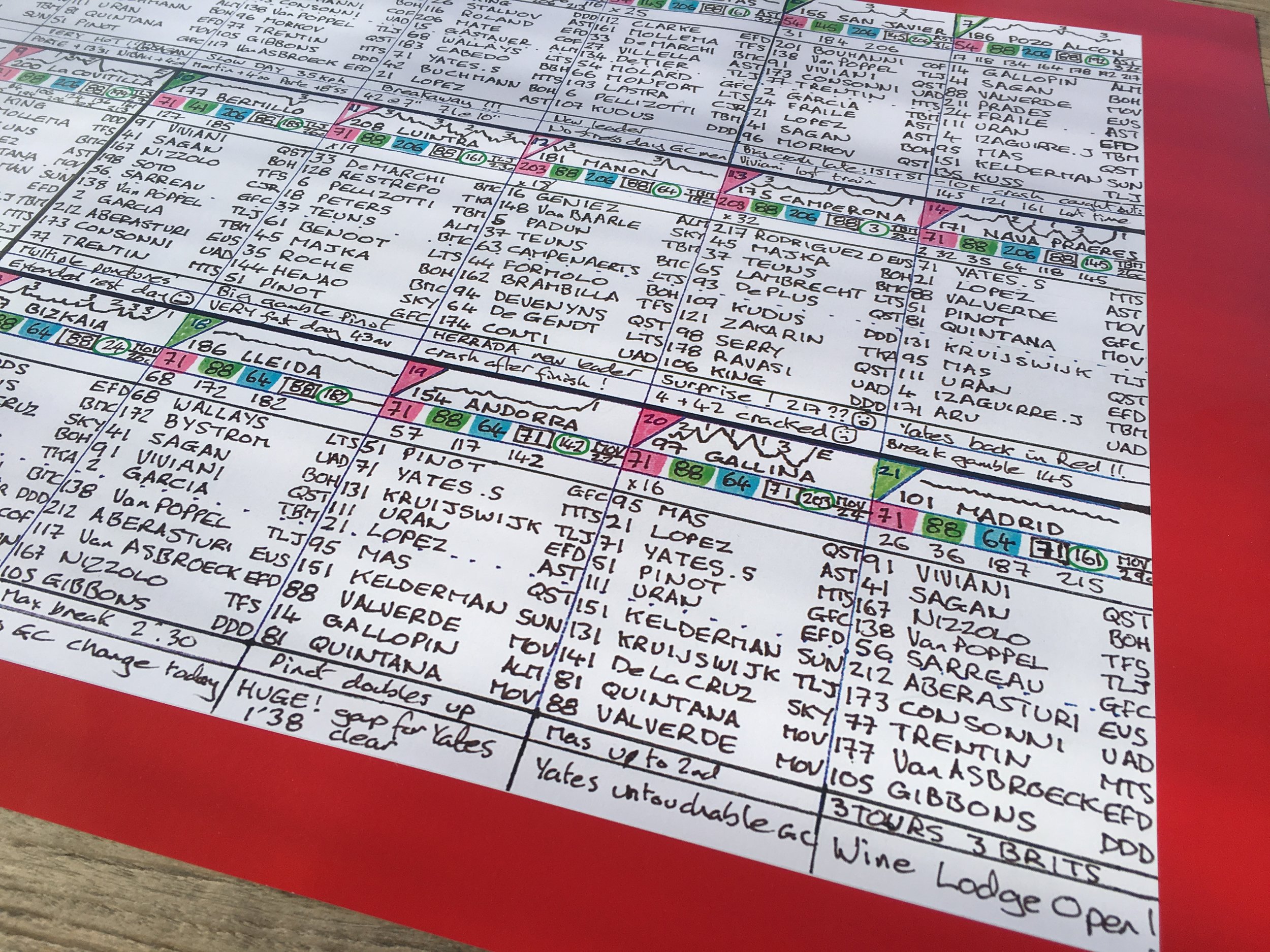

Coppi and Bartali had a legendary rivalry

Bartali kept very quiet about his exploits during the war. It was only when his son, Andrea, was in his thirties, that he began talking about it on a visit to Assisi to see the Giotto frescoes. Bit by bit, Bartali began to recount snippets of some heroic deeds that he remained modest about throughout his life. It was only in 2012, 12 years after his death, with the publication of a book, “Road To Valour,” that the true extent of the courage he showed during the war began to fully emerge.

To go back to Bartali’s historic victory in the Tour de France in 1938 reveals where his loyalties lay. Mussolini wanted to use his victory as a sign that Italians belonged to a noble Aryan race, declaring him a true “Aryan Champion.” Bartali refused to be a symbol for the Italian fascists however, and in his rejection, insulted both Mussolini and the party. Furthermore he publicly made a statement that “The world is the homeland for all human beings,” in direct contrast to the edicts being passed at the time which expelled all Jewish children from school.

Between 1938 and 1943, the Jews suffered persecution from the Italian authorities, but it was nothing like on the scale inflicted on Jewish people in Northern Europe. Many were sent to camps, but these were almost open prisons. When the Allies began their invasion from the south, the country became split into two, with German forces and an Italian puppet government ruling the Northern half. With that, the treatment of the Jews reverted to SS and Gestapo methods. Jews still remaining in the north of the country were rounded up and sent off to the concentration camps of Birkenau and Auschwitz.

It was at this time that Bartali took in Giorgio Goldenberg and his Jewish family, sheltering them in the basement of his house in Florence. In doing so he was not only risking his but his family’s life. If they were caught there would have been an immediate execution without trial, a fate that befell many others.

Bartali was a deeply religious man and his exalted status in Italy meant that he had contacts at the very top of the Catholic Church. It was through his friendship with the Archbishop of Florence that he became involved in a secret organisation, the Assisi network and DELASEM, a Jewish resistance organisation.

"Do good, don’t talk about it.”

Bartali would go for long training rides from Florence to DESALEM’s headquarters in Genoa where he would pick up fake ID and documentation. He’d hide these inside the steel tubes of his bike and cycle back, stopping at the monasteries and convents that were secretly sheltering Jewish refugees within their walls to deliver the papers. In this way hundreds of Jews were able to escape south by travelling on false travel documentation.

This secret alliance between Jews and the Catholics who sheltered them happened all over Italy. In the film, “My Italian Secret: The Forgotten Heroes” a survivor speaks of how a nun gave him a crucifix to fool the German guards looking for Jews. So intent was she that he wouldn’t betray his true religion that she insisted he kiss her ring, not the cross, while the guards loomed over to check. A Mother Superior would stand behind the guards mouthing the words of the Lord’s Prayer or Hail Mary as the children were forced to prove their Christianity.

Italy’s greatest cyclist of the era was so well known that his bike training ruse worked perfectly. He would wear his famous jersey, emblazoned with BARTALI across the front and carry a spare tyre, pump and a spanner which he used to remove his seat stem to hide the travel documents and fake IDs. If he was stopped he would merely say that he was on a training ride. If the guards became inquisitive about his bike he would tell them not to touch it because it was such a finely tuned racing machine that any small adjustment would wreck it. In this way he transported hundreds of documents that saved hundreds of lives, risking certain death if he was caught.

Wherever Bartali went he would be mobbed by hundreds of fans and he would use this fame to effect. Terontola was an important train station in Tuscany as it linked the north and south. By appearing on the platform a huge crowd would quickly build up around him as everyone tried to talk to him, touch his clothes or just get a glimpse of their hero. The German guards would have to leave their posts to disperse the crowd, and in so doing would allow dozens of escaping Jews to climb aboard trains heading south.

Bartali remained reticent about his involvement while he was alive. He said that he kept silent about it out of respect for those who did more than he did. “I don’t want to talk about it or act like a hero,” he said. “Heroes are those that died, who were injured, who spent many months in prison.” Andrea remembers how his father used to tell him: “You must do good, but you must not talk about it. If you talk about it you’re taking advantage of other’s misfortunes for your own good. Do good, don’t talk about it.”

A survivor of the time reflects that, “It’s a beautiful story of people who never boasted about what they did. They did it simply because it needed to be done. Even to their families they never let on and they never asked for anything in return.”

For many of us, sports people are everyday heroes that we admire, wish to emulate, sometimes worship. But thinking about Gino Bartali risking his life on a daily basis during the war must surely put that into a different perspective. Not only was he a cycling Great, but a man with a profound sense of humanity and an almost childlike sense of ‘what’s right’ that he couldn’t see any other way. And his modesty (something he wasn’t always known for on the bicycle) remain, for me, the defining characteristic of a true hero.