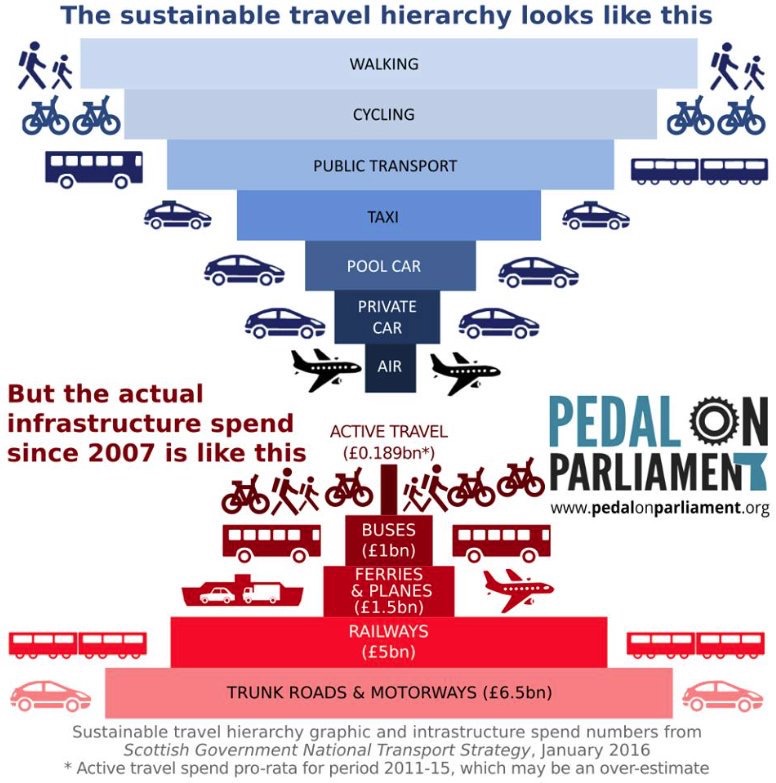

Speaking to The Times this week, Chris Boardman asked how Britain can call itself a cycling nation when the current government invests £1 a head per year (as opposed to £24 a head in Holland) in cycling infrastructure.

“It gets me angry,” he said. “It’s insulting that it’s even called an investment strategy. Over £600 million to refurbish Bank tube station and the government invests £300 million across the entire country spread over five years for cycling and walking… ‘Insulting’ is the word.”

Chris Boardman is 'angry'

Boardman’s frustration is shared by many of us, especially when you consider that the arguments for investing in cycling are so strong on so many levels: pollution, health, business. “It’s the most cost-effective form of transport you can make,” he asserts.

The government’s reluctance to properly invest in and encourage cycling is confusing. Speaking at Spin London last week, Boardman was non-plussed himself, and said that it must be the Treasury who are just blinkered and can’t see it. But our reliance and devotion to the car was explained with clarity some forty years ago by the philosopher and Catholic priest, Ivan Illich.

Philiosopher Ivan Illich

Some of Illich’s most interesting ideas can be found in his 1974 work, “Energy and Equity” which proposes the concept of ‘counter-productivity’ when institutions of modern industrial society impede their purported aims. For example, he calculated that, in 1970s America, if you add the time spent to work to earn money to buy a car, the time spent in a car (including traffic jams), the time spent in hospitals because of accidents, the time spent in the oil industry and so on, and you divide that by the number of kilometres travelled per year per person, the average speed of each car journey is in fact only 6km per hour.

Even without taking into account the amount of time spent working to pay for a car, the average rush hour speed among cars in Central London is about the same as a horse drawn cart in the 1800s and less than that of the modern cyclist.

And that bike takes up such little space. As Illich says, eighteen bikes can be parked in the space of one car. Thirty can move along in the space taken by a moving car. To move 40,000 people across a bridge in an hour requires twelve lanes of cars, four by bus, three by train and only two by bicycle.

If houses were designed like cities...

As we have become slaves to the car our cities have evolved in a way that no one would have ever designed them in the first place. To make room for cars we have sacrificed an enormous amount of our personal space. A child cannot play in the street and is restricted to their personal garden, if they have one, or must go to a designated park or play area to which they may have to be driven to. Our Victorian streets were never designed to have cars parked either side of them for their entire length.

Victorian streets were not designed for cars

In the suburbs, people can’t get around conveniently because they are far away from everything. To make room for cars, distances have increased. People live far away from school, from work, from the supermarket. The car wastes more time than it saves and creates more distance than it overcomes.

If we continue our slavish reliance on the car the only logical conclusion is to further develop our cities in the image of Los Angeles or other sprawling urbanizations. They are splintered communities, strung out along empty streets lined with identical developments, designed for driving as quickly as possible from work to home and vice versa. In some American streets the act of strolling in the streets at night is grounds for suspicion of a crime.

Why is it that in British society, the city, once regarded as a modern marvel, is now seen as a living hell, a place to escape from? Another philosopher from Illich’s era, Andre Gorz, made the point that, the car, of course, and the accompanying noise, smell, pollution and danger it creates has made our cities uninhabitable. To escape we need faster cars to travel motorways to satellite towns far away. “What an impeccable circular argument!” he says. Give us more cars and wider roads so we can escape the destruction caused by cars and polluted streets!

Why should we have a place for work, a separate place for living, another for shopping, a fourth for education and yet another for entertainment? The way our space is divided up disintegrates society. Transport policy is not an issue that should be decided on remotely, by itself, but as a wider plan for how we live as human beings, as parts of a social community.

“People,” writes Illich, “will break the chains of overpowering transportation when they come once again to love as their own territory their own particular beat, and to dread getting too far away from it.” But for this to be possible we have to make the city habitable and not trafficable. We need to reinvigorate neighbourhoods into real communities again which are shaped by the varied activities therein : working, living, learning, relaxing, communicating, managing a coexistence and finding a life in common.

This really should be at the crux of transport policy. We can make arguments about the health benefits of getting people on their bikes and the amount of money it will save citizens and the government in the long run. These are good points and have been made many times. And ignored. We need politicians with vision who have the courage to do something about improving the quality of life of its citizens in a more profound way.

Last month Barcelona announced ambitious plans to reduce traffic by 21%, freeing up 60% of streets currently used by cars to turn them into so-called "citizen spaces". The plan is based around the idea of mini neighbourhoods around which traffic will flow, and in which spaces will be repurposed to "fill our city with life."

Forget the little concessions, tax breaks here and there and incentives to do this or that. We need to be rebuilding our cities to make them vibrant, local, real places again. And you can’t do that as long we remain enslaved by the car.