A few years ago three cycling obsessed geeks, two American and one Australian, published the Velominati Rules. It was a tongue in cheek manifesto of how a road cyclist should be, laying down the law on how to dress, ride and behave on the bike.

Probably their most famous rule has become #5: Harden the Fuck Up, a motto that has been liberally plastered over mugs, jerseys and posters as well as being shouted out on many a club run. In honour of that phrase they have now published a book that celebrates the toughest cyclists of all time.

Divided up into sections for Rouleurs (all-rounders), Grimpeurs (climbers), Klassiekers (one-day specialists), Domestiques (team workers) and Velocisti (sprinters), it recounts the exploits of “35 of the most heroic Cyclists ever.” Ironically, as David Millar points out in his articulate foreword, it’s about the bike racers who made up their own rules. “Because, as much as each of us must learn the rules from others at the beginning, it is only when we make them our own that we become hard.”

What is it about cycling and suffering that lures us so? The Velominati describe the ability to persist in the face of intense suffering as a state of mind, bordering on a lifestyle. “Suffering liberates us from our daily lives…To ride our bikes and suffer by our own choice is to take control, if only for a short while, and escape into a more simple world.” That, I’m sure, strikes a chord with many of us.

Almost as soon as people started to race each other on bikes, it became a standard that the riders should be pushed to the very limits of human endurance, and, as a result, cyclists have become measured by how far they are prepared to suffer as much, if not more, by how skillful they are on the bike. By celebrating the careers of the hardest cyclists, the book is less concerned with the results that they achieved than the qualities they showed on the road: their panache, heroism and humanity. It’s this that excites us when we watch a grueling Grand Tour or monstrous one-day race over mud-spattered cobbles, through sheets of rain.

Frank Strack, Editor-in-Chief of The Velominati

So it was that I delved into this book, licking my lips at the prospect of reading some tales about the hardest of hard riders. I wasn’t disappointed.

Firstly, a note about the style of writing. Frank Strack, the founder of Velominati, has a witty, casual and often sharp turn of phrase. Quoting Lance Armstrong’s famous line that “pain is temporary, quitting lasts forever” Strack redeems himself by adding that “even assholes can be insightful.” Writing about a photo of Jan Raas, the Dutchman who won both Roubaix and Flanders twice, not to forget his three world championships, with his “black shorts just barely containing the Guns of Navarone” and “custom glasses with holes drilled around the outside to de-fog them better as he crushed fools,” he reminds us that this is what champions looked like before they looked like Chris Froome. Quite!

What’s more, despite many of these accounts of brutal endurance and suffering being well-known already, Strack knows how to tell a story. Each account remains fresh, often amusing and always impressive. The chapter on Pantani is celebratory rather than the more common maudlin accounts of his downfall while still identifying his vulnerability and flawed nature – this is why he remains one of the most popular riders of all time.

Hardmen

Strack has included quite a few women in his list of Hardmen including Marianne Vos, Lizzie Armitstead, Rebecca Twigg and Nicole Cooke and he acknowledges that they should have a higher profile on TV and the media. Writing about the women’s Olympic road race in 2012, he describes it being way more exciting than the men’s race and he celebrates the finale between Vos and Armitstead. But it’s Queen Lizzie’s courage in speaking up for women’s cycling at the end of it that is also acknowledged here.

I was reminded of little anecdotes that I’d forgotten along the way like the one of Hinault who ran over a dog, apparently deliberately, when it got in his way. His belligerence, aggression and determination to continue after crashing seven times on Roubaix are astounding. “He was just one badass French mofo…and his stature, akin to some sort of stray French mongrel bulldog. If Hinault were a dog, or even an actual badger, he’d definitely be limping, missing an eye and ready for the next fight.”

Then there’s Beryl Burton who casually offered a stick of liquorice to poor Mike McNamara as she overtook him on the twelve-hour time trial. Her record of 38.5 kph over twelve hours stands to this day.

The Velomninati’s choice of riders is pretty good, with a mix of characters from the distant past as well as more recent tough men and women. Merckx, Roche, Kelly of course all feature. Then Quintana, Jens Voigt and Mathew Hayman represent the more modern era.

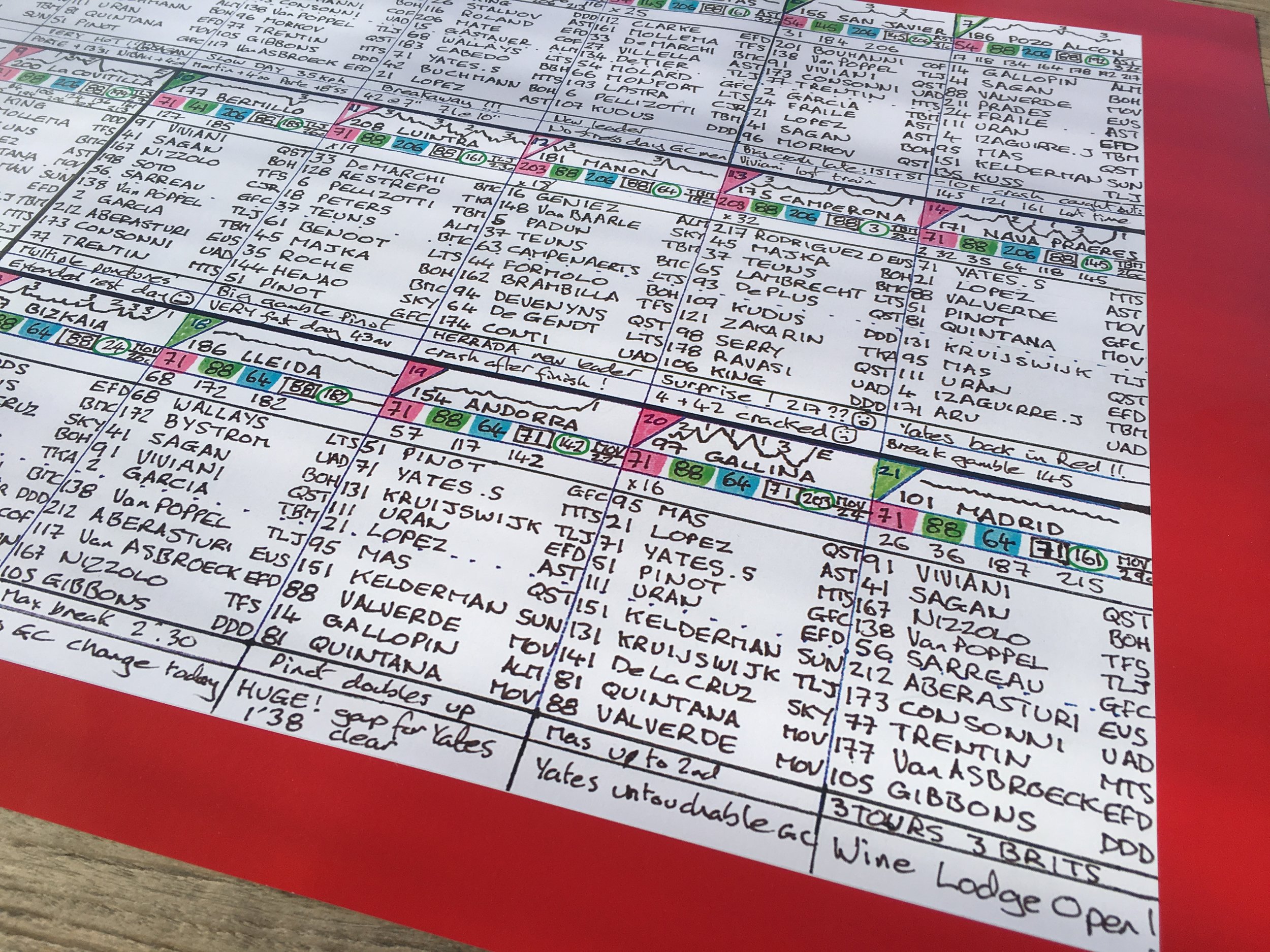

The Velominati have greatest respect for the Spring Classics

The book is a thoroughly enjoyable read split up into short, manageable sections making it ideal to dip in and out of. The boyish enthusiasm with which the riders are described reflects the sincere respect and admiration the Velominati clearly have for the Hardmen of the peloton. That relish and innocent love of the sport comes through time and again – they just get the whole contrast between the pain and beauty of cycling that makes it so irresistible. Not to mention the aesthetics of what a good bike rider should look like. “Photos of Merckx, De Vlaeminck, Moser all show them with elbows bent, back flat, torso pulled low…” That’s what we should be aiming for.

The appealing thing about the Velominati, and I wish people would get this when they quote The Rules, is that they don’t take themselves seriously. Addressing the issue of who has been left out, “There are a variety of explanations, some of which include things like ‘would have required research’ or ‘forgot about them until we finished.’”

So, best not to approach this with too much earnestness as that’s definitely not the tone in which it’s written. It’s an unharnessed, joyous celebration of the best bits of cycling. Vive la vie Velominatus!

The Hardmen: Legends of the Cycling Gods by The Velominati is published by Pursuit Books on 1st June