As Tom Dumoulin lost two minutes of his lead in the Giro d’Italia on Tuesday as a result of a mistimed ‘comfort break’, fans and commentators were up in arms about the fact that his rivals took advantage of him being caught short. To many it seemed that the likes of Nibali, Zakarin and Quintana were breaking some of the age-old unwritten rules of professional cycling - that you don’t exploit a rider’s mechanical (or other) misfortune, especially when they’re wearing the leader’s jersey.

There can be few toilet breaks to have sparked such a torrent of social media traffic. Cycling Weekly’s Dr Hutch questioned whether the flying Dutchman was taking marginal gains to the next level by dropping a bit of weight just before the final climb of the day. In a separate tweet he commented, “Poor old AG2R. They’ve been wearing brown shorts for years, waiting for just such an event.” The Giro leader has been referred to as ‘Poomoulin’, pictures of toilet roll hanging from a saddle went viral and one joker posted a photo of a toilet cistern attached to a bike frame. One Rijcko Treep simply said, “Shit happens.”

Dumoulin strips off at the side of the road

But, while some saw the funny side, others were outraged that the peloton appeared to exploit the Pink jersey’s misfortune. Quintana and co were accused of unsporting behaviour and a lack of respect for the leader of the race. Their actions transgressed an honourable code, one that has marked out cycling as a more noble sport than others. Dumoulin’s stony face and remarks of disappointment at the finish line suggested that he agreed.

A stony faced Dumoulin just retained the Pink Jersey

Reaction from professional commentators such as Eurosport’s Sean Kelly and Brian Smith was mixed. While they suggested that it would have been a good gesture to slow the pace and allow Dumoulin to catch up with the other GC contenders, they also accepted that the outcome of the whole stage would have been completely different. Sky’s Mikel Landa was in a breakaway a couple of minutes up the road and the day’s victory would have been his for the taking. As it was, Nibali’s hair raising descent into Bormio meant he was able to catch the Basque rider and eventually outsmart and outsprint him to the finish line. It was a thrilling climax to a hugely entertaining and exciting day of racing.

The Italian tifosi were delighted at the first Italian stage win by one of their countrymen in this year’s giro. But some neutral observers have commented it’s a sign that professionalism has taken over from the gentlemanly conduct that has governed the sport for so many years. Is it an outdated code that harks back to a romantic, more amateur era? And what are those unwritten rules, anyway, and have they really always been adhered to in the way that some have claimed?

Charly Gaul and Louison Bobet

Vincenzo Nibali said after Tuesday’s stage, “If we look at the history of cycling, go back through the record books, I think you’ll find that some very similar things have happened.” He’s not wrong: back in the 1956 Giro, Charly Gaul made an indecent gesture while taking a pee break to Louison Bobet, a rider he hated. Miffed by the insult, Bobet instructed his team that they were to attack straight away. They sped off leaving Gaul standing there. With echoes of Dumoulin’s situation a few days ago, Charly Gaul had a weak team that were unable to pace him back into the race meaning that he lost eight minutes on the day and his chance of winning Pink. He got his revenge the following day by teaming up with Gastone Necini and leading him up the final mountain stage, ultimately giving him a 19 second advantage over Bobet.

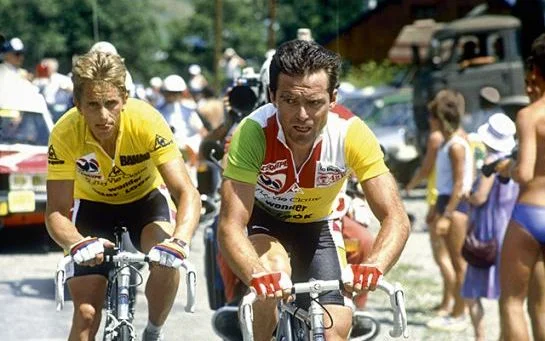

LeMond and Hinault

Perhaps aware that his rivals, particularly Benard Hinault, would take advantage of his stomach trouble in the 1986 Tour de France, Greg LeMond continued riding when he was afflicted by chronic diarhoea. Richard Moore describes in “Slaying The Badger” in graphic detail what happened.

“Taking the small cotton team cap, LeMond shoved it down his shorts, maneuvered it into position, and filled until it was overflowing. He tried to clean himself up, but it was hopeless; then he tossed the hat into the hedgerow, and began the grim task of getting back into the race, slotting in behind three teammates who’d dropped back from the peloton to wait for him.”

Of course, it’s not only a race leader’s toilet break that can be exploited. There is an unwritten rule that major GC contenders afflicted by mechanical problems, crashes and punctures should be given time to get back in the race. Jan Ullrich famously waited for Lance Armstrong on Luz Ardiden in the 2003 Tour after the Texan was brought down by a spectator. It was a noble gesture and one wonders if it ever comes back to haunt him – Armstrong won the stage.

Ullrich waited for Armstrong

It was, in fact, pay-back for when Armstrong waited for Ullrich two years earlier when the German crashed coming down the Peyresourde in the 2001 Tour. “I’m really grateful for Jan for remembering my gesture two years ago,” said Armstrong. “ What goes around comes around.” Louison Bobet would have understood what he meant.

Armstrong was one of those charismatic characters of the peloton who took on the role of ‘patron’ or leader of the race. He was one of a long list of charismatic leaders that stretches back from Hinault, Merckx and Anquetil, all the way back to the very first Grand Tours. These were feats of endurance and the only way to survive was to accept the will of the Patron who imposed a set of rules of basic decency. But perhaps there just isn’t the same kind of leadership in today’s peloton. Have the likes of Chris Froome got the authority that riders from other teams will respect? Probably not.

Ultimately, a rider who doesn’t respect the old rules will probably come to regret it in the future when the tables are turned. But then, as Nibali said after Tuesday’s stage win, “I’m very straightforward: I never expect anyone to wait for me when I stop. Many times, I’ve fallen or punctured and just set of again.” He can probably expect that treatment to continue.